I used to like Ascension-tide. It’s upbeat. It’s concrete. It’s something to celebrate: Jesus is King. Our guy won. The world is his oyster.

But lately I’ve begun to worry about it and wonder whether we should maybe even take it off the calendar. Fact is, they have down graded it. It used to be called “the Sunday after the Ascension” but now that’s only the subtitle and the real name is “the Seventh Sunday of Easter.” I think we’re a little nervous about the Ascension these days There’s the whole up/down problem of the three-storey universe but I also wonder whether it conveys a message of domination in a world where that’s a dangerous model. I mean, do we really need to hold up the idea of power as good in a world where power is usually bad?

I remember reading an essay a long time ago by an English theologian in which he puzzled over the way Americans accept the idea of Jesus as king. He said in effect, “Here we have a whole country full of people insisting on democracy and yet completely untroubled by the idea of Jesus as king.” Well, why is it that we still go slightly crazy over Prince Harry and roll out the red carpet for royal visitors? We fought a war to be rid of royalty and then we welcome the royals back even though most of them are hardly role models for anyone? Why are we so willing to accept the notion that Jesus is King? As if royalty and power were something wonderful?

And it’s not just Ascension Day by any means and not just the word King. To use the name “Jesus Christ” is to say it again. Christ means King, so Jesus Christ is King Jesus and what does that really say about our relationship with God and our relationships with each other? Think  about it.

about it.

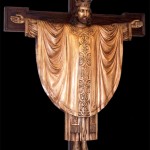

Well, begin by thinking about Jesus. Can you read the gospels and come away with a picture of Jesus as King? Again and again people tried to push that role on him and again and again he resisted. In the gospel of John, it says: “When Jesus realized that they were about to come and take him by force to make him king, he withdrew again to the mountain by himself.” When Pilate asked Jesus: “Are you the king of the Jews?” Jesus never gave a direct answer. He said, “I came to bear witness to the truth.” And did he act like a king? Did he in any way imply that he had come to take power? When he entered Jerusalem, the royal city, he rode in on a humble donkey and yes, people hailed him as king but I see nothing in the story that implies a desire for royal power. No, the story is one of humility, the rejection of power, and when Pilate nailed a sign to the cross that said, This is Jesus, the King of the Jews, it was intended to be a sneer at the Jews – this crucified criminal is a Jewish king – but it also summed up, it seems to me, exactly what Jesus thought of kingship: a useless title, an empty honor, a symbol supreme of the worthlessness of human power. And the gospel of John seems to say that if you want to see what human power is like, what kingship is really like, you should look at the cross. Jesus said, “I, if I be lifted up, will draw all people to myself.”

But is it the crown or the cross that has become the fundamental symbol of Christianity to which we have been drawn? We know the answer. But have we ever really tried to apply it? I think you could argue that this country did. We created a country without a king, a unique experiment. You have to wonder why it took so long for people to make the experiment because certainly the Bible provides a constant critique of the whole notion of kingship. Way back in the Old Testament there’s a story known as Jotham’s Fable about a time when the trees decided to have a king. And they asked the olive tree to be king and the olive tree said, Should I stop producing oil in order to be your king? And they went to the vine and asked and the vine said “Should I stop making grapes for wine to come and be your king?” And so it went until they came to the harsh and useless thorn bush and the thorn bush became their king.

Fast forward almost 3000 years and you come to Alexis de Tocqueville, the French philosopher and politician who wrote a study of American life almost 200 years ago that is still studied today. He commented on the fact that in America “there was so much distinguished talent among the citizens and so little among the heads of the government.” That was almost 200 years ago and it seems to be still true, doesn’t it? But isn’t that exactly the point that Jotham’s fable is making: the kings of this world, rulers of this world, are people not much good for anything else. I hate to be cynical about government but it’s awfully hard to be positive, isn’t it? As our coins say: In God we trust – not in human leaders.

And that’s the story of the Old Testament: once upon a time, there was no king in Israel because they were subject only to God. But then they came to a point where they insisted on having a king so they could “be like other people.” And Samuel warned them what a king would be like. “A king,” he said, “will take your sons and daughters to be his servants and take your wealth to embellish his court” But they insisted, We will have a king so we can be like other people. and so they were given kings who fought wars like other kings until the country was destroyed. And they never had another king but they survived while other nations with powerful kings disappeared. Why, then, would they still have hailed Jesus as king? Why, then, do we still call him the Christ, the king? Why do we use the terms of human power in seeking a relationship with the spiritual? Haven’t we seen by now how destructive – and unconstructive – human power can be?

A year ago this time – how soon we forget – we were in the midst of our quadrennial election cycle and struggling with the issue of what we know or need to know or want to know or don’t want to know about how power has been used by those we have elected. Power corrupts – Lord Acton’s summary of human experience is there in the Bible to be read. Jesus knew it, and avoided it, and never claimed to be king. And here we come hailing him as king and I see no good solution to it until someone writes new hymns and new prayers as joyful and positive as the old ones. But I do think we can do two things now: one, look for better images for our relationship with God and two, look for better role models around us than we generally get from politics and the media.

Let me take the second one first. I was talking with a college student a while ago about her career goals and they were good ones. She wanted to do the kind of work our society needs but doesn’t pay for. And I quoted my favorite slogan about career goals, the words of an English philosopher (C.E.M.Joad) who said, “The purpose of a liberal arts education is to enable you to despise the wealth it prevents you from acquiring.” I was delighted to discover that she knew the saying and had even seen it up-front in one of her text books. It occurs to me that we might describe Christianity as intended to help you despise the power that can destroy your soul.

Why should it be that even in a democracy there is still so much corrupting power? Why should we have a system in which money is the controlling influence? What would Jesus say? If we know the answer to that, and I think we do, then can we find a relationship with Jesus more in keeping with his teaching and his life? I think we can.

Start with the gospel story – the whole gospel: what does it show Jesus doing? Do you see any evidence in him of a hunger for power, a desire for people to kneel before him, any interest in titles, any slightest implication that he asks us to treat him like royalty? Then how do we come into a relationship with Jesus? What images can we use? If you had been in first century Palestine, what would have happened? I can imagine Jesus walking through town, stopping in a house here or an office there, chatting with people at the Bantam Market, giving them a hand with their groceries. The relationship is one of friendship – unlimited self-giving friendship that takes Jesus into places not considered respectable – where would those be in Bantam and Litchfield? – and into relationships with people not considered respectable. Power hungry people don’t act that way. But Jesus wasn’t out for power, he was seeking friendship with us. So friendship is one basic model for our relationship with Jesus and our relationships with others.

Or what about the image Jesus used of a vine and branches? “Abide in me,” Jesus said. It’s a relationship of shared life, a relationship with Jesus that incorporates him into our daily lives, in our hearts, on our mind, always within us – relationships with each other of shared life. That’s one model for our relationship with Jesus: the vine and the branches.

Then there’s also the sacrificial model: the cross. Jesus died for us, gave himself for us and that’s perhaps the most critical model for us to hold up for ourselves and for our world. When was the last time a politician called on you for self-sacrifice: we’ve been asked to prosecute a war without raising taxes and cut back on services, schools and health care and safety rather than raise taxes. Wouldn’t it make sense if we love our country to be asked to sacrifice for it? Isn’t that democracy is all about? You don’t expect kings to be self-sacrificing, to turn down the thermostat in the palace, to invite the poor and the hungry in to share their wealth, but isn’t that the model Jesus gives us? St Paul said it best, I think, in the Letter he wrote to the Christians in Philippi: “Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death– even death on a cross. Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend.” Yes, every knee should bend as we humble ourselves to serve our world as Jesus served and serves us.

So it’s Ascension-tide, let’s celebrate. But let’s remember also that this Jesus we hail came among us in poverty, descended all the way down to us before he ascended on high, and became our Lord through his humility, through his death, his total self-giving of himself for us. So let’s find ways to hold up that model, the model Jesus gave us, a way of life that rejects power but seeks humbly, sacrificially of living for our community, our friends, our world, and seeks to live in him and let him live in us.