A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at All Saints Church, San Francisco, on Good Shepherd Sunday, Easter IV, May 12, 219.

Up until six years ago I lived in the northwest corner of Connecticut, an area of small towns and small farms and I served a parish in the town of Canaan which liked to claim that it had more cows than people. Somehow I got into a conversation one day with a retired farmer about the relative intelligence of sheep and cows. He told me cows are smarter: they know when to come home and they even know their own stall. The farmer told me about a visit he had from a city friend who was surprised by the way the cows would come into the barn and go straight to their own stalls. And the farmer told him, “That’s why we have those plaques on each stall with each cow’s name on it, so they can find their own stall more easily.”

Well, cows may be smart, but not that smart. Sheep are not smart at all. But Jesus used them as an example because sheep are a lot like human beings, they’re a lot like us. There’s a form of confession in the Prayer Book in Morning Prayer Rite One that says it in so many words: “we have erred and strayed from thy ways like lost sheep.” We, like sheep, have a tendency to err and stray from the way. The cowherd claps his hands and calls Bossy and Bossy comes. The sheep just keep on munching. The shepherd needs a crook to pull the sheep back from danger and the crook has a pointed end to prod the sheep in the right direction. The shepherd needs a good sheep dog if possible to run around and bark at the sheep and nip at their heels to get them moving the right way because without all that help the sheep would get lost. Sheep just focus on the next blade of grass and keep on munching as long as they see that next blade of grass until they’re hopelessly lost. Sheep are not smart.

So Jesus chose a relatively stupid animal to illustrate God’s love for us. When he compares us to sheep it’s not a compliment! Jesus is saying we are like sheep: we tend to wander, we lack much inner guidance, we have a tendency to get lost, we’re apt to get into trouble. It’s not, as I said, a compliment, but it is probably a fair assessment. Yeah, human beings are like that. I’ve met a few of them. I read about them in the paper. I see them on television. It makes you wonder. And, to be honest, I know myself well enough to recognize that Jesus was right. Maybe you’ve had some experience along these lines yourself.

But the other side of the coin is that for all of that, nevertheless, God loves us, God values us. The sheep may be dumb but they have commercial value so the shepherd exerts himself to save them. The shepherd would not exert himself for the sheep if there weren’t some value there: wool, mutton, lamb chops. Very few people raise raccoons. The sheep have a value to the shepherd. And the implication is that we have a value to God. Is that obvious? Probably not. When you stop to think of the billions of people crowding the planet, living very often in conditions that no self-respecting sheep would put up with, and put that in the perspective of a span of creation in which the human lifespan is insignificant and a span of space in which this earth is a grain of sand, who could imagine that a Creator would care? And yet, the Bible makes that claim. It not only makes that claim, it goes way beyond that: it says that we are made in the image of God; that we are in some essential way like God.

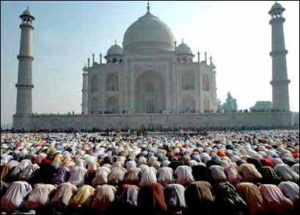

You and I and the people of Kathmandu are like God. Sheep are not much like the shepherd; they’re a different order of being. No number of sheep can change a light bulb; they can’t even find their way home. But the Bible claims that we are like God in some essential way.

I shouldn’t do this, but I can’t resist. On the subject of light bulbs: how many Episcopalians does it take to change a light bulb? Two: one to change the light bulb and one to reminisce about how much they liked the old one. That’s also relevant to the Rector search process you’re involved in. But I digress.

The Bible claims that we are like God in some essential way, and therefore God values us as we would value our own children. The Bible speaks of God as loving us, yearning for us, grieving over us and finally entering into our lives and living here among us and dying for us.

Now, what that also means is that God in some essential way is like us. It always surprises me when I have the chance to speak with a couple planning to be married and find out that they haven’t the foggiest idea what God is like. They have some vague idea of a distant, impersonal power – what the movies call “The Force” – which is not something I much relate to. What is “The Force.” Can you fall in love with a Force or imagine a Force that sees you as anything more than another force, and an insignificant force in the larger picture, a minor force to be absorbed or manipulated or annihilated?

Of course, we use force ourselves – sometimes well, sometimes badly – but force is a tool and our relationship with force is to control or be controlled. The Force is a tornado destroying homes, an earthquake wiping out a city, a military invasion, a cancer. A force is many things but none of them loveable. God is not like that. Nor did Jesus ever use language like that about God. God in Jesus’ teaching is sometimes a powerful king but more often a forgiving father, a careful housewife, a hen with chickens, a shepherd with sheep, one who cares for the birds of the air and the lilies of the field and knows our needs and loves us. It’s not a particular compliment Jesus pays us in comparing us with sheep, but it is a wonderful gift: God cares; God values us; God loves us.

Now that’s good to know but it’s not the whole story. It comes with a job to do. The Gospel speaks of other sheep who must also be brought so that finally there is one flock and one shepherd. I’ve had many a disagreement over the years with well-meaning Christians who wonder why we should spend our time worrying about foreign mission and trying to convert people to our faith when they have a perfectly good faith of their own. Well-meaning but totally confused. Does it make a difference to you to know God loves you? Wouldn’t it matter to someone else as well? Someone once described the church’s mission as being like that of hungry beggars who know where bread is to be found and tell others.

Is there really no difference between, for example, Christianity and Islam, between a religion of submission and a religion of freedom, between a religion of a distant God and the knowledge of a close and loving God? Yes, we have things in common: we worship one God, and we know God is merciful. But we also have vast differences. Muslims are for the most part, a peaceful people and we shouldn’t judge them by the worst examples. I don’t want Christianity to be judged by the fundamentalists who think the world is flat and was created 4000 years ago and we shouldn’t judge Islam by ISIS. But there is a difference between Islam at its best and Christianity at its best. And we have a mandate to share what we know.

There are people who think it’s fine to get all the marbles and keep them. There are others who seem to know instinctively that gifts are given to be shared. The Gospel surely, is a gift to be shared. In the early years of the Christian Church there were people called Gnostics who believed that there was secret knowledge available only to insiders and initiates. You couldn’t be given the secret knowledge unless you proved yourself worthy over a long time of training. Gnosticism won a good many followers for awhile; it’s nice to think you’re in on a secret and that you’ve earned the right to special status. But Gnosticism was condemned as a heresy. Christianity is not like that. Christianity is not a secret wisdom for the chosen few; it’s about a love that needs to be shared, shared with everyone, no holds barred.

Christianity is open and available and there for the taking and if that means that the church is filled with people who don’t seem quite nice or quite as deserving as we are – well, that’s the way Jesus and his disciples seemed to a lot of people in that time also. “Why does your master eat with publicans and sinners?” they asked. “If this man is a prophet, how come he’s doesn’t know what kind of woman it is that he’s talking to?” That was the criticism. And Jesus accepted that criticism. He said, “The well have no need of a doctor but only those who are sick.” He said he came for the sick. He told his disciples to go into all the world, not stay home where it’s safe, not keep it a secret, but go find those other sheep who are no more or less sheepish than you are; find them and bring them home to the God who loves them and wants them to know that love.

We are members of a church that in all too many congregations these days works hard to balance the budget and has all too little left for others. It may be that we have our priorities wrong, that we need to get mission into our budget first and then see whether we have anything left over for ourselves because the job isn’t done just because the doors are open on Sunday. Jesus did not say, “I’m waiting here with the door open.” The Good Shepherd doesn’t stand there waiting for the lost sheep to come back; the Good Shepherd goes looking. There’s work to be done and we’ve barely begun to do it. So there’s good news in today’s gospel but there’s a challenge also: God loves us – but not just us. Our God is the Good Shepherd who loves us all and seeks to bring us all home and calls us not just to be sheep but to help with the shepherding and help make God’s love known.

How many Episcopalians does it take to change a lightbulb – ha ha. and thanks, will use it in my church where the dinosaurs refer to the Alter, and the refrain is we’ve done things this way (wrong) for 27 years.